No sooner do I get home from a week away that I head out for an evening again, the SFS in a mostly-Sibelius program. I regret I was still too tired from the trip to take this in completely, and the brief opening piece, Nautilus by Anna Meredith, went right by me. But I knew the Sibelius pieces and they connected.

With Joshua Bell as soloist, the Violin Concerto turned entirely to butter. Tasty, smooth butter, but butter nonetheless. Bell's actually rather elaborate solo style dominated the proceedings, but the orchestra under guest conductor Dalia Stasevska melted in kind. Quiet, uneventful, unaggressive, a kindly background for the fancy but undemonstrative solo work.

This wasn't the Stasevska who came back after intermission for the Second Symphony. Especially in the finale, here we heard SFS in its full amazing blazing glory, winds and brass shining to the stars, the way MTT would do it. Not unimportantly, the flow was coherent, with each surge meaning something and not repetitious.

But the general buildup of the piece was much more unusual. Stasevska kept pulling back on the volume and intensity, rendering quiet passages so as to build it up again the more effectively later. It jumped back and forth this way. If it had concentrated just on the finale, I could read it as a way of diluting the threatening pomposity - which was most effectively diluted. But the whole symphony was like that, and the placement of the pull backs was not obviously to pull back on the buildup; rather the opposite. A most unusual, if effective, treatment.

Stasevska is about the shortest conductor I've ever seen. This wouldn't be relevant except that conductors are supposed to be tall in order to be masterful. Well, here's proof that a short woman can be just as masterful as any tall male.

Saturday, April 29, 2023

Thursday, April 27, 2023

the Randy Byers memorial road trip

As long as I was going to Seattle, I determined to take a couple days and drive out to the deep countryside of the western side of the enormous Olympic Peninsula. I hadn't been in that area since childhood, and accounts by my friend the late Randy Byers had encouraged me. Even before he became ill, Randy found relief from the stresses of his job responsibilities at the UW in what he called the "nature therapy" of short vacations out on the Pacific coast there. Ever since I heard him mention that, I'd wanted to take a look myself.

Randy's favorite place was the tiny town of La Push, center of the Quileute Nation. It's on the coast at the mouth of a river, and as you stand on the beach in town and look out, you can see the peculiar islands of the type called "stacks" that decorate the Washington state coast. They're detached pieces of land with sheer sides and flat tops with usually trees growing on top, as if they were part of the landbound forest, and they look like this:

And the surf rolls in and the waves make their whooshing sound and it's just a relaxing place to be. That's what you go there for: like many Indian towns, La Push is mostly a collection of randomly-placed prefab houses. I didn't see a motel, though there appeared to be some apartments for rent. There's one restaurant, where I was hoping to have lunch but it was closed for repairs or something.

La Push is at the end of a 15-mile dead-end road that comes off the highway (US 101, not much of a highway in that back country, one lane in each direction) at the town of Forks, which does have motels but is best known as the setting for Twilight. They didn't film the movies there, though, and I understand why. Forks is a dingy old timber town with nothing much to it, though I did enjoy the town museum with its photo of the young local men who formed an engineer battalion and went off to apply their lumbering trade in construction on the Western Front in WW1.

I saw nothing relating to Twilight in Forks, although on the road to La Push was a small resort with a sign in front reading "No Vampires Beyond This Point."

I also got to the rain forest tucked up in the Hoh River valley deep inside the national park, about 20 miles up from the highway, another place Randy visited and found rewarding. Vegetation everywhere. Ferns and grasses blanketing the forest floor, so thick that the only chance a tree has to grow is to fasten itself on a fallen log which subsequently decays. And when the trees grow, mosses come and drape themselves over the branches. They're not parasites on the trees, they just rest there and take their moisture and nutrients from the cold but humid air. It looks rather like this:

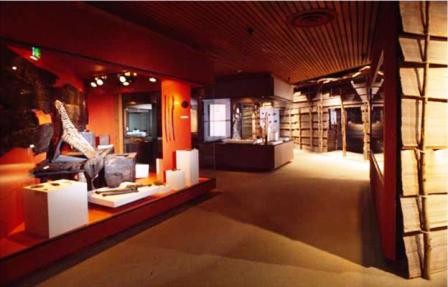

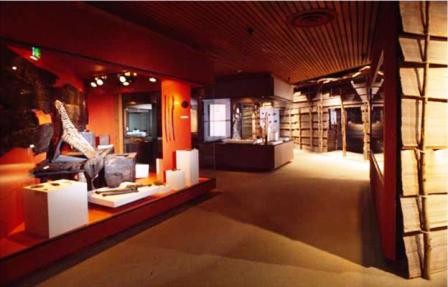

Randy also took the very long and twisty drive - about 70 miles - to Neah Bay, on Cape Flattery the westermost point of the 48 states, and so did I. It's another Indian town, the home of the Makah Nation, who've erected a very impressive museum of their culture. Forced to move away from their original village in the days of assimilation, they lost much of their traditional culture. But a few decades ago, a major storm unearthed a lot of artifacts from the original village site. Anxious to preserve them, the Makah contacted some archaeologists who'd been friendly to them and organized an excavation, and many of the finds are now in the museum. From this the Makah learned, for instance, that they'd been fishing with nets since before the assimilation period, so this is part of their traditional culture.

On the road to Neah Bay, out in the countryside but not far from Port Angeles, is a little cafe specializing in blackberries. Not only may you have blackberry pie for dessert, but you can have your hamburger with a blackberry-infused bbq sauce. Yum.

Randy's favorite place was the tiny town of La Push, center of the Quileute Nation. It's on the coast at the mouth of a river, and as you stand on the beach in town and look out, you can see the peculiar islands of the type called "stacks" that decorate the Washington state coast. They're detached pieces of land with sheer sides and flat tops with usually trees growing on top, as if they were part of the landbound forest, and they look like this:

And the surf rolls in and the waves make their whooshing sound and it's just a relaxing place to be. That's what you go there for: like many Indian towns, La Push is mostly a collection of randomly-placed prefab houses. I didn't see a motel, though there appeared to be some apartments for rent. There's one restaurant, where I was hoping to have lunch but it was closed for repairs or something.

La Push is at the end of a 15-mile dead-end road that comes off the highway (US 101, not much of a highway in that back country, one lane in each direction) at the town of Forks, which does have motels but is best known as the setting for Twilight. They didn't film the movies there, though, and I understand why. Forks is a dingy old timber town with nothing much to it, though I did enjoy the town museum with its photo of the young local men who formed an engineer battalion and went off to apply their lumbering trade in construction on the Western Front in WW1.

I saw nothing relating to Twilight in Forks, although on the road to La Push was a small resort with a sign in front reading "No Vampires Beyond This Point."

I also got to the rain forest tucked up in the Hoh River valley deep inside the national park, about 20 miles up from the highway, another place Randy visited and found rewarding. Vegetation everywhere. Ferns and grasses blanketing the forest floor, so thick that the only chance a tree has to grow is to fasten itself on a fallen log which subsequently decays. And when the trees grow, mosses come and drape themselves over the branches. They're not parasites on the trees, they just rest there and take their moisture and nutrients from the cold but humid air. It looks rather like this:

Randy also took the very long and twisty drive - about 70 miles - to Neah Bay, on Cape Flattery the westermost point of the 48 states, and so did I. It's another Indian town, the home of the Makah Nation, who've erected a very impressive museum of their culture. Forced to move away from their original village in the days of assimilation, they lost much of their traditional culture. But a few decades ago, a major storm unearthed a lot of artifacts from the original village site. Anxious to preserve them, the Makah contacted some archaeologists who'd been friendly to them and organized an excavation, and many of the finds are now in the museum. From this the Makah learned, for instance, that they'd been fishing with nets since before the assimilation period, so this is part of their traditional culture.

On the road to Neah Bay, out in the countryside but not far from Port Angeles, is a little cafe specializing in blackberries. Not only may you have blackberry pie for dessert, but you can have your hamburger with a blackberry-infused bbq sauce. Yum.

Sunday, April 23, 2023

Sondheim Festival V: Sweeney Todd

(I also went to see a concert performance of Follies - that's no. IV - but to my surprise my review of that isn't up yet.)

This is, oh, the third or fourth time I've seen Sweeney Todd staged, and it's by far the biggest. Enormous cavernous old theater in Seattle, large elaborate sets (but not elaborate enough: see below) with what look from a distance like tiny actors moving around on it, and the sine qua non of pretentious musical shows, dim lighting.

Full theater orchestra, actors miked up the wazoo so their voices won't get drowned out, pretty good performances. Yusuf Seevers doesn't seem quite powerful enough to make an ideal Sweeney. On the other hand, Deon'te Goodman as Anthony is enormously powerful. Maybe they should have switched parts. (They're both Black, by the way. So are Leslie Jackson as an effective Johanna and Porscha Shaw as a somewhat less effective Beggar Woman.) Anne Allgood as Mrs. Lovett is at her best being deadpan, even while singing. Sean David Cooper is a sufficiently evil Judge Turpin, which isn't always easy to pull off.

It was hard to avoid the impression they should have sent out for somebody who knew something about staging. Sweeney's victims, after he cuts their throats, each get up out of the barber chair and walk across the room to the trap door so that they can fall into it. WTF? As for the final scene with the baking oven ... yeah, that didn't quite work either.

Still, a good enough show to make you leave the theater humming. The ravenously appreciative audience on a Saturday night was mostly made up of young people, some of them dressed in variations on Victorian demimonde.

This is, oh, the third or fourth time I've seen Sweeney Todd staged, and it's by far the biggest. Enormous cavernous old theater in Seattle, large elaborate sets (but not elaborate enough: see below) with what look from a distance like tiny actors moving around on it, and the sine qua non of pretentious musical shows, dim lighting.

Full theater orchestra, actors miked up the wazoo so their voices won't get drowned out, pretty good performances. Yusuf Seevers doesn't seem quite powerful enough to make an ideal Sweeney. On the other hand, Deon'te Goodman as Anthony is enormously powerful. Maybe they should have switched parts. (They're both Black, by the way. So are Leslie Jackson as an effective Johanna and Porscha Shaw as a somewhat less effective Beggar Woman.) Anne Allgood as Mrs. Lovett is at her best being deadpan, even while singing. Sean David Cooper is a sufficiently evil Judge Turpin, which isn't always easy to pull off.

It was hard to avoid the impression they should have sent out for somebody who knew something about staging. Sweeney's victims, after he cuts their throats, each get up out of the barber chair and walk across the room to the trap door so that they can fall into it. WTF? As for the final scene with the baking oven ... yeah, that didn't quite work either.

Still, a good enough show to make you leave the theater humming. The ravenously appreciative audience on a Saturday night was mostly made up of young people, some of them dressed in variations on Victorian demimonde.

Friday, April 21, 2023

concert review: Seattle Symphony

Creating a soundtrack for Sergei Eisenstein's 1925 silent film Battleship Potemkin by stuffing together wads from various Shostakovich symphonies is such an obvious idea that it's been done at least three separate times. I heard one of these, played against a showing of the movie, from the San Francisco Symphony some years ago.

Now I'm in Seattle, listening to a different one. This one was concocted, and is conducted by, a German conductor named Frank Strobel. He's set it to a restored version of the movie. Potemkin has been edited and censored so much that most prints are incoherent hash. This one was more like a movie, with characters and a plot. Most refreshing.

Strobel is more creative with his Shostakovich than his predecessors. Like them, he sets the Odessa Steps sequence to the Winter Palace Massacre music from the Eleventh. But he makes the parts fit the sequence better. He edits the original slightly, then when he runs out of music from it he switches briefly to the climax of the slow movement from the Fifth, and then back to a repeat of the same music from the Eleventh. The closing scene, in which the Potemkin thinks it'll have to fire on the rest of the Russian navy, is to the staccato scherzo from the Eighth, and when they discover the other ships are also full of revolutionaries it switches to the climax from the finale of the Fourth and manages to work that into an ending.

This concert was fantastically easy to get to and I only wish I could do this at home. I'm staying within walking distance of one of the new stations on the light rail line. I hop in (the cars are more like SF Muni streetcars than BART cars) and 15 minutes later emerge directly in the lobby of the concert hall itself - fantastic! And far easier than the hour that the freeway signs were saying it would take to drive the 8 miles into town at afternoon rush hour + parking. My only complaint is that the concert hall is at about the primitive lemur stage of evolution regarding understanding the concept of signage.

Now I'm in Seattle, listening to a different one. This one was concocted, and is conducted by, a German conductor named Frank Strobel. He's set it to a restored version of the movie. Potemkin has been edited and censored so much that most prints are incoherent hash. This one was more like a movie, with characters and a plot. Most refreshing.

Strobel is more creative with his Shostakovich than his predecessors. Like them, he sets the Odessa Steps sequence to the Winter Palace Massacre music from the Eleventh. But he makes the parts fit the sequence better. He edits the original slightly, then when he runs out of music from it he switches briefly to the climax of the slow movement from the Fifth, and then back to a repeat of the same music from the Eleventh. The closing scene, in which the Potemkin thinks it'll have to fire on the rest of the Russian navy, is to the staccato scherzo from the Eighth, and when they discover the other ships are also full of revolutionaries it switches to the climax from the finale of the Fourth and manages to work that into an ending.

This concert was fantastically easy to get to and I only wish I could do this at home. I'm staying within walking distance of one of the new stations on the light rail line. I hop in (the cars are more like SF Muni streetcars than BART cars) and 15 minutes later emerge directly in the lobby of the concert hall itself - fantastic! And far easier than the hour that the freeway signs were saying it would take to drive the 8 miles into town at afternoon rush hour + parking. My only complaint is that the concert hall is at about the primitive lemur stage of evolution regarding understanding the concept of signage.

Wednesday, April 19, 2023

three concerts

1. I was sent to review the Mission Chamber Orchestra. Unusual repertoire, rare composers I'd heard before, but whom I'd never reviewed. I keep an index of my reviews, and find that I've now covered 500 different composers in my professional reviews. Most-seen name on the list, Beethoven of course, with 74 reviews.

2. Emerson String Quartet, on their farewell tour after nearly fifty years of grinding away at the circuit. A fundamental program, with Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. A highly traditional approach, the kind of superficially featureless playing that I heard on a lot of recordings in my younger days and which made me think I didn't like chamber music. The glories here were subtle: in individual notes and the handing off of parts between the instruments, and that's something you need to learn to listen for. Still, the Second Razumovsky (the Beethoven piece) did achieve an overall shape of beauty, especially in the slow movement. I'd have liked to hear these guys play Op. 132 like that, but you can't have everything.

3. Two young Brits, violinist Tamsin Waley-Cohen and pianist James Baillieu, in a program featuring CPE Bach. Three pieces, all of which sounded completely different and none of which were at all like his symphonies, which is what I like him for. Illuminating and strange.

Also on the program, a Duo by Schubert which was hopped up to the extent that it didn't sound at all like Schuberts. Maybe he was on amphetamines. Schubert can surprise you: did I tell you about his Mass that sounded like Philip Glass? And Romances by Schumann, which I seized on as a lifeline because I'd actually heard at least one of these before.

2. Emerson String Quartet, on their farewell tour after nearly fifty years of grinding away at the circuit. A fundamental program, with Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. A highly traditional approach, the kind of superficially featureless playing that I heard on a lot of recordings in my younger days and which made me think I didn't like chamber music. The glories here were subtle: in individual notes and the handing off of parts between the instruments, and that's something you need to learn to listen for. Still, the Second Razumovsky (the Beethoven piece) did achieve an overall shape of beauty, especially in the slow movement. I'd have liked to hear these guys play Op. 132 like that, but you can't have everything.

3. Two young Brits, violinist Tamsin Waley-Cohen and pianist James Baillieu, in a program featuring CPE Bach. Three pieces, all of which sounded completely different and none of which were at all like his symphonies, which is what I like him for. Illuminating and strange.

Also on the program, a Duo by Schubert which was hopped up to the extent that it didn't sound at all like Schuberts. Maybe he was on amphetamines. Schubert can surprise you: did I tell you about his Mass that sounded like Philip Glass? And Romances by Schumann, which I seized on as a lifeline because I'd actually heard at least one of these before.

Friday, April 14, 2023

Mike Foster

I ought to say a word for Mike Foster, a Mythopoeic Society stalwart who died at the age of 76 on Wednesday. He was a voluble contributor to festivities, and in recent years was most celebrated for his contribution to the Lord of the Ringos shows, scratch performances of mostly sixties pop and rock songs with new Tolkien-reference lyrics. But his best work was elsewhere.

For decades, Mike taught English literature at a community college in central Illinois, which gave him the opportunity to introduce generations of students to the study of Tolkien, and made him just about the most experienced Tolkien professor out there. At the big 50th anniversary of The Lord of the Rings conference at Marquette University, where the papers are held, Mike gave a talk bristling with intelligent and clever ideas of how to teach Tolkien.

For instance, he outlined the papers he assigned in his Tolkien class. First, an analysis of any chapter - of the student's choice - from any of Tolkien's major works: how it contributes to the story. Second, a study of a work Tolkien might have read and its possible influences. Third, an evaluation of any full-length critical study. And last, a study of the evolution of one particular character.

But my favorite line of Mike's - one I refer to often - was one he occasionally noted on an essay: "That happened in the film you obviously saw, not in the book you were supposed to have read."

For decades, Mike taught English literature at a community college in central Illinois, which gave him the opportunity to introduce generations of students to the study of Tolkien, and made him just about the most experienced Tolkien professor out there. At the big 50th anniversary of The Lord of the Rings conference at Marquette University, where the papers are held, Mike gave a talk bristling with intelligent and clever ideas of how to teach Tolkien.

For instance, he outlined the papers he assigned in his Tolkien class. First, an analysis of any chapter - of the student's choice - from any of Tolkien's major works: how it contributes to the story. Second, a study of a work Tolkien might have read and its possible influences. Third, an evaluation of any full-length critical study. And last, a study of the evolution of one particular character.

But my favorite line of Mike's - one I refer to often - was one he occasionally noted on an essay: "That happened in the film you obviously saw, not in the book you were supposed to have read."

a bifurcated day

I've done this combination before, but not for a few years. Life gets more challenging as you totter on.

Thursday was the day I drove over the Hill (the Hill, between the Valley and the Water) to the UC Santa Cruz library to spend the day ransacking its databases for the Tolkien Studies bibliography. I'd been working on that in the public databases at home for most of the last week, and now was the time to turn to the proprietary ones that only universities have. The interfaces for these have been changing again, and it's getting more difficult in library catalogs to get access to what we catalogers call the 245c, which is what lists the credits from the title page. With sloppier rules for name entries, you now can't tell whether the names presented are authors, editors, the writers of the preface, or what, or what form of name they use in the actual book.

I had to leave early because the arboreal effluvia from last month's storms is still being cleared up, and I wanted to get through before the crews started closing the mountain road's lanes for the day. I arrived by 9:30, bought my day parking pass, and spent five hours, relieved only by bathroom breaks, at a public terminal working away: a typical amount of time for this. Now my thumb drive is stuffed with PDFs, which the Year's Work writers will find useful next year.

That gave me enough time to grab a quick late lunch before driving up the long coast road to the City for a SF Symphony concert. That was what I could have used a little rest before engaging with. It was a mostly-Baroque evening conducted by Jane Glover, mostly-Baroque specialist. Bach's Magnificat, much briefer than the St. Matthew Passion thank the Lord, tiny orchestra vastly outnumbered by giant chorus but still drowning them out half the time. Reconstructed Bach concerto, solo parts played by the orchestra's concertmaster and principal oboe. Handel's hearty and tuneful Music for the Royal Fireworks, accompanied by 1) amusing account in the program book about what a disaster the first performance in 1749 was; 2) short new work written as its homage, depicting fireworks by running broadly-paced, thinly-scored brass and wind lines over busy strings. Called Spectacle of Light by Stacy Garrop. Refreshingly light sound, though that's not the kind of light the title means.

Home around 11 pm, to find a Tybalt expecting to be compensated in attention for what he missed by my being gone all day.

Thursday was the day I drove over the Hill (the Hill, between the Valley and the Water) to the UC Santa Cruz library to spend the day ransacking its databases for the Tolkien Studies bibliography. I'd been working on that in the public databases at home for most of the last week, and now was the time to turn to the proprietary ones that only universities have. The interfaces for these have been changing again, and it's getting more difficult in library catalogs to get access to what we catalogers call the 245c, which is what lists the credits from the title page. With sloppier rules for name entries, you now can't tell whether the names presented are authors, editors, the writers of the preface, or what, or what form of name they use in the actual book.

I had to leave early because the arboreal effluvia from last month's storms is still being cleared up, and I wanted to get through before the crews started closing the mountain road's lanes for the day. I arrived by 9:30, bought my day parking pass, and spent five hours, relieved only by bathroom breaks, at a public terminal working away: a typical amount of time for this. Now my thumb drive is stuffed with PDFs, which the Year's Work writers will find useful next year.

That gave me enough time to grab a quick late lunch before driving up the long coast road to the City for a SF Symphony concert. That was what I could have used a little rest before engaging with. It was a mostly-Baroque evening conducted by Jane Glover, mostly-Baroque specialist. Bach's Magnificat, much briefer than the St. Matthew Passion thank the Lord, tiny orchestra vastly outnumbered by giant chorus but still drowning them out half the time. Reconstructed Bach concerto, solo parts played by the orchestra's concertmaster and principal oboe. Handel's hearty and tuneful Music for the Royal Fireworks, accompanied by 1) amusing account in the program book about what a disaster the first performance in 1749 was; 2) short new work written as its homage, depicting fireworks by running broadly-paced, thinly-scored brass and wind lines over busy strings. Called Spectacle of Light by Stacy Garrop. Refreshingly light sound, though that's not the kind of light the title means.

Home around 11 pm, to find a Tybalt expecting to be compensated in attention for what he missed by my being gone all day.

Tuesday, April 11, 2023

theatrical review

When my brother and I toured northern New England some 15 years ago, one of our more intriguing visits was to the Haskell Free Library, which is a public library deliberately built in 1904 on the international border between Derby Line, Vermont, and Stanstead, Quebec. The entrance is in the U.S., but most of the library is in Canada; a dark line down the floor marks the border.

The idea was to commemorate and exemplify the freedom along the "longest undefended border" in the world, but by the time we got there, it was no longer undefended. Canadians could only reach the entrance by walking a specified route and promising to return immediately upon leaving. Jersey barriers blocked the residential streets that casually crossed the border, and swarms of US border patrol guards lurked around, ready to pounce upon and question anybody who looked suspicious, like a couple of geography-buff brothers who were poking around the neighborhood to see exactly where the border ran.

So I was mightily curious to see a play set there. World premiere plays can be a very hazardous proposition, but this one was good. It's called A Distinct Society, and it's by Kareem Fahmy, a Canadian-born writer of Egyptian descent. It's set just after the Trump travel ban of 2017, which made things worse. The library became kind of a neutral zone, just about the only place where - to take the characters presented in this play - a man from Iran, free to enter Canada but not the U.S., could meet his daughter who's in the U.S. on a student visa but can't leave the country. According to the play, some blogger using the name Elizabeth Bennet let the world know about this and it became popular, so the border patrol is cracking down: visits only five minutes, and no passing along gifts.

The other characters in the play are the librarian, who's just trying to keep the peace (but who's a Jane Austen fan; hm, interesting); a border guard, who has the sweets on the librarian and is not very enthusiastic about the restrictions but is under heavy job pressure to enforce them; and a truant high school student, whose enthusiasm is for Green Lantern comics, excuse me graphic novels, and is always pulling moral lessons out of them to educate the other characters. As the title suggests, the history of Quebec separatism also makes an appearance. It was about an hour and a half, no intermission, well acted, dragged very little. I liked it and am glad I went. Running in Mountain View to the end of April.

The idea was to commemorate and exemplify the freedom along the "longest undefended border" in the world, but by the time we got there, it was no longer undefended. Canadians could only reach the entrance by walking a specified route and promising to return immediately upon leaving. Jersey barriers blocked the residential streets that casually crossed the border, and swarms of US border patrol guards lurked around, ready to pounce upon and question anybody who looked suspicious, like a couple of geography-buff brothers who were poking around the neighborhood to see exactly where the border ran.

So I was mightily curious to see a play set there. World premiere plays can be a very hazardous proposition, but this one was good. It's called A Distinct Society, and it's by Kareem Fahmy, a Canadian-born writer of Egyptian descent. It's set just after the Trump travel ban of 2017, which made things worse. The library became kind of a neutral zone, just about the only place where - to take the characters presented in this play - a man from Iran, free to enter Canada but not the U.S., could meet his daughter who's in the U.S. on a student visa but can't leave the country. According to the play, some blogger using the name Elizabeth Bennet let the world know about this and it became popular, so the border patrol is cracking down: visits only five minutes, and no passing along gifts.

The other characters in the play are the librarian, who's just trying to keep the peace (but who's a Jane Austen fan; hm, interesting); a border guard, who has the sweets on the librarian and is not very enthusiastic about the restrictions but is under heavy job pressure to enforce them; and a truant high school student, whose enthusiasm is for Green Lantern comics, excuse me graphic novels, and is always pulling moral lessons out of them to educate the other characters. As the title suggests, the history of Quebec separatism also makes an appearance. It was about an hour and a half, no intermission, well acted, dragged very little. I liked it and am glad I went. Running in Mountain View to the end of April.

Monday, April 10, 2023

happy holidays

It's been Easter. It is also, and still is, Pesach. Accordingly, I spent my weekend at two celebratory dinners in the mid to late afternoons. To both of these, my contribution was broccoli: I've found that the simplest steamed broccoli, seasoned only with a few herbs, is as popular and gratefully accepted as any fancier version I could make.

Saturday was an excellent choice for a seder, being the only available convenient date I could attend. This was, as usual, with the family of old friends who've adopted me and a few other individuals without convenient seder-hosting families of our own. Eleven adults at this table, some 6 or 7 mostly of the next generation at the other. The usual chatty gathering with lots of conversation about our doings and those of mutual acquaintances. I fastened on a bottle of moscato rosa wine as my beverage of choice for the ritual four glasses of wine, and when that ran out, the other bottle. Main course, lamb.

Sunday for Easter was unusual. The usual hosts for family gatherings, our niece and nephew T. & T., weren't here. Their son N. is now a freshman at Case Western, so they'd gone off to Cleveland to be with him. OK ... I didn't go nearly that far from home for university, but part of the point was to establish an identity for myself and be out from under my parents' apron-strings. I wouldn't have wanted them to descend on me for a holiday; when I wanted to celebrate with them, I came home, which for Christmas is what N. did.

Substitution was provided by another nephew, T.'s brother L., and his wife E. Often gone to celebrate holidays with E.'s family, they were at their gratifyingly nearby home this time, along with the other local brother and his wife, plus parents of all of the above siblings, plus one set of aunt and uncle, that's us, making eight. Very comfy quarters, lots of chocolate, the traditional "hunt" for plastic Easter eggs in the front yard (the trick is, pretending you don't immediately see them all), a large meal (main courses, ham and chicken), and a game of Boggle for those who didn't prefer to nap.

Saturday was an excellent choice for a seder, being the only available convenient date I could attend. This was, as usual, with the family of old friends who've adopted me and a few other individuals without convenient seder-hosting families of our own. Eleven adults at this table, some 6 or 7 mostly of the next generation at the other. The usual chatty gathering with lots of conversation about our doings and those of mutual acquaintances. I fastened on a bottle of moscato rosa wine as my beverage of choice for the ritual four glasses of wine, and when that ran out, the other bottle. Main course, lamb.

Sunday for Easter was unusual. The usual hosts for family gatherings, our niece and nephew T. & T., weren't here. Their son N. is now a freshman at Case Western, so they'd gone off to Cleveland to be with him. OK ... I didn't go nearly that far from home for university, but part of the point was to establish an identity for myself and be out from under my parents' apron-strings. I wouldn't have wanted them to descend on me for a holiday; when I wanted to celebrate with them, I came home, which for Christmas is what N. did.

Substitution was provided by another nephew, T.'s brother L., and his wife E. Often gone to celebrate holidays with E.'s family, they were at their gratifyingly nearby home this time, along with the other local brother and his wife, plus parents of all of the above siblings, plus one set of aunt and uncle, that's us, making eight. Very comfy quarters, lots of chocolate, the traditional "hunt" for plastic Easter eggs in the front yard (the trick is, pretending you don't immediately see them all), a large meal (main courses, ham and chicken), and a game of Boggle for those who didn't prefer to nap.

Thursday, April 6, 2023

how stupid can you get?

So John Scalzi posted that he's looking for a science researcher to help with his next novel, and among the areas of expertise he wants the researcher to help with are:

Did this person not read the opening phrase of my post? Did they not read Scalzi's "not necessarily relating to the Earth's moon"? Do they have trouble understanding what the word "not" means? How could they possibly have read my post, which discusses the Moon, and thought I didn't know what the word "selenology" means? Isn't it obvious that I'm a step ahead of you and am asking how you apply it beyond the basic dictionary meaning which I know perfectly well and which I do the courtesy of assuming that the readers do too? Or is this person a lazy incapable reader who saw a post with questions and the word "selenology" in it, and assumed without reading it that the question must be not knowing what "selenology" means?

I'm kind of stunned by the degree of ignorance it must take to draw that meaning out of my post. Or, if it was sheer laziness and not bothering to read the post, why they then bothered to take the time to display what they thought was their superior learning.

Sorry, but this degree of ignorance and condescension masquerading as superior learning in the form of things too basic to need to be explained - it really frosts me.

- Selenology (generally, not necessarily relating to the Earth's moon)

- Geology (generally, not necessarily relating to the Earth)

If they're not being restricted to the Earth and our Moon, then what exactly is the difference between geology and selenology? Is it an arbitrary distinction between planets and moons? Or does it mean "bodies that physically resemble the Earth/Moon"? (e.g. that one has plate tectonics and an atmosphere and the other doesn’t)Is that clear? Apparently not to the person who next commented, who so helpfully explained,

Selenology is the study of the geology and features of the moon and how it came to be. There is a lot of info available on this.Unfortunately the thread was already a couple of days old and Scalzi closed it before I saw this and could reply, so I'll expostulate here instead:

Did this person not read the opening phrase of my post? Did they not read Scalzi's "not necessarily relating to the Earth's moon"? Do they have trouble understanding what the word "not" means? How could they possibly have read my post, which discusses the Moon, and thought I didn't know what the word "selenology" means? Isn't it obvious that I'm a step ahead of you and am asking how you apply it beyond the basic dictionary meaning which I know perfectly well and which I do the courtesy of assuming that the readers do too? Or is this person a lazy incapable reader who saw a post with questions and the word "selenology" in it, and assumed without reading it that the question must be not knowing what "selenology" means?

I'm kind of stunned by the degree of ignorance it must take to draw that meaning out of my post. Or, if it was sheer laziness and not bothering to read the post, why they then bothered to take the time to display what they thought was their superior learning.

Sorry, but this degree of ignorance and condescension masquerading as superior learning in the form of things too basic to need to be explained - it really frosts me.

Wednesday, April 5, 2023

two string quartet concerts

I signed up to hear the Chiaroscuro and Modigliani Quartets, both at Herbst four days apart, because they were both playing some of my favorite early 19C repertoire. Each had a Beethoven and a Schubert. Chiaroscuro played Beethoven's Op. 95, which is probably his gnarliest, and Schubert's one-movement "Quartettsatz", but their major piece was Mendelssohn's Op. 13, a tribute to late Beethoven that's my favorite Mendelssohn quartet. Modigliani played Beethoven's Op. 18 No. 3, probably his lightest and most cheerful, and gave the major spot on the program to Schubert's huge and dark "Death and the Maiden" Quartet, filling out the program with Puccini's tiny memorial piece Chrysanthemums.

Chiaroscuro's gimmick is that they play on old-fashioned gut strings. Or so they say. The sound was boxy and woody, as you'd expect from that claim, but they played in such a modern manner, fast and more concerned with drama than with emotional expressiveness, that this negated the antiquity of the sound quality. I wonder about the authenticity here. The players didn't retune anywhere near as much as verified gut-string players I've heard. Maybe their strings were gut-wound instead. While their Beethoven and Schubert were fine, it was the Mendelssohn that conveyed a sense of the spread and depth of the piece.

Modigliani's style is smooth and clear. They sailed so placidly through the charming Beethoven that I wondered if they'd have anything saved up in their emotional box for Schubert. It turned out they mustered up volume and vehemence just fine; what was missing was emotional impact, a sense of tragedy. It wasn't a hollow performance, just not as affecting as it was arresting.

And next week, it's the Emerson Quartet with another similar program, with Beethoven plus Haydn and Mozart instead of Schubert. And that'll be my last Herbst concert of the season.

Chiaroscuro's gimmick is that they play on old-fashioned gut strings. Or so they say. The sound was boxy and woody, as you'd expect from that claim, but they played in such a modern manner, fast and more concerned with drama than with emotional expressiveness, that this negated the antiquity of the sound quality. I wonder about the authenticity here. The players didn't retune anywhere near as much as verified gut-string players I've heard. Maybe their strings were gut-wound instead. While their Beethoven and Schubert were fine, it was the Mendelssohn that conveyed a sense of the spread and depth of the piece.

Modigliani's style is smooth and clear. They sailed so placidly through the charming Beethoven that I wondered if they'd have anything saved up in their emotional box for Schubert. It turned out they mustered up volume and vehemence just fine; what was missing was emotional impact, a sense of tragedy. It wasn't a hollow performance, just not as affecting as it was arresting.

And next week, it's the Emerson Quartet with another similar program, with Beethoven plus Haydn and Mozart instead of Schubert. And that'll be my last Herbst concert of the season.

Sunday, April 2, 2023

another 48-hour Shakespeare play festival

Silicon Valley Shakespeare does this annually: giving teams each with 4 actors, a writer, and a director 48 hours to write and rehearse a 10-minute skit based on a given Shakespeare play and employing a given premise, each different for each skit, and then perform them before an audience when the 48 hours are up. I've seen these before, and they can be pretty funny.

This year they were played in the tiny theater at the local college, which suited the premise much better than last year when they were in the cavernous large theater. Instead of being mostly empty, the audience seating was packed.

This year the premises were Shakespeare plays in various historical settings. The winner of the audience appreciation vote was The Comedy of Errors in the Wild West. This was a pretty straightforward adaptation, with Antipholus the sheriff facing Antipholus the bank robber, with the usual confusion over which Dromio belongs to which. It was the director's idea to have the characters' spurs (which the actors weren't actually wearing) make noise, so every time somebody walked they'd say "ching, ching, ching ..." Although the highlight was the human tumbleweed, for which the actor tucked up her knees, grabbed them with her hands, and formed a ball which rolled across the stage.

My favorite was Julius Caesar set in the 1990s, in which Casca, having made a threatening phone call, murders Julia Caesar (played by a woman) two days early, having gotten confused over when the Ides of March were. (In some months, the Ides actually are the 13th.) When Brutus and Cassius complain, Casca suggests they just prop Caesar's body up as if it were alive, but that's shot down on the grounds that Weekend at Bernie's was an Eighties movie and this is supposed to be the Nineties.

Other entries, all of them at least passingly amusing, were A Midsummer Night's Dream in the Ice Age, in which the only character actually from the play was Puck, played by a pre-teen boy, whose best line was, "My job is to create chaos and complicate your lives, and believe me, it's not that hard to do"; As You Like It as high-school truants in the 1980s, the best-acted of the bunch; and a Much Ado in which Beatrice and Benedick keep arguing even while on the block to be executed in the French Revolution.

This year they were played in the tiny theater at the local college, which suited the premise much better than last year when they were in the cavernous large theater. Instead of being mostly empty, the audience seating was packed.

This year the premises were Shakespeare plays in various historical settings. The winner of the audience appreciation vote was The Comedy of Errors in the Wild West. This was a pretty straightforward adaptation, with Antipholus the sheriff facing Antipholus the bank robber, with the usual confusion over which Dromio belongs to which. It was the director's idea to have the characters' spurs (which the actors weren't actually wearing) make noise, so every time somebody walked they'd say "ching, ching, ching ..." Although the highlight was the human tumbleweed, for which the actor tucked up her knees, grabbed them with her hands, and formed a ball which rolled across the stage.

My favorite was Julius Caesar set in the 1990s, in which Casca, having made a threatening phone call, murders Julia Caesar (played by a woman) two days early, having gotten confused over when the Ides of March were. (In some months, the Ides actually are the 13th.) When Brutus and Cassius complain, Casca suggests they just prop Caesar's body up as if it were alive, but that's shot down on the grounds that Weekend at Bernie's was an Eighties movie and this is supposed to be the Nineties.

Other entries, all of them at least passingly amusing, were A Midsummer Night's Dream in the Ice Age, in which the only character actually from the play was Puck, played by a pre-teen boy, whose best line was, "My job is to create chaos and complicate your lives, and believe me, it's not that hard to do"; As You Like It as high-school truants in the 1980s, the best-acted of the bunch; and a Much Ado in which Beatrice and Benedick keep arguing even while on the block to be executed in the French Revolution.

Saturday, April 1, 2023

Tolkien in Vermont

The University of Vermont has been holding a small annual Tolkien conference for ages now, and I'd have liked to attend were it not for the extreme exertions required to get to Vermont from here. However, this year they did it hybrid. (Apparently last year also, but I didn't hear about it.) So I signed up. That did mean getting up at 5:30, but this is something I normally do. However, going back for a nap is something else I normally do, so I only caught about half of the 15 presenters.

Very good stuff, though, focusing on obscure literature of Middle-earth's Second Age. Gratifyingly advanced presentations, assuming the auditors knew not only Tolkien's writings in detail but the scholarly literature as well. I particularly liked two papers performing some deep character analysis of Aldarion and Erendis. I claim that Erendis is Tolkien's greatest female character. If she's unfamiliar to you, you should read Unfinished Tales, which I think is the posthumous Tolkien book that the most fans of The Lord of the Rings would most like. I've written about her myself, but mostly to introduce her to the unfamiliar, not at the advanced level heard here.

A couple speakers, including the keynoter, explored a topic which has gotten a lot of discussion over the years, the internal sources of the history. Who is telling the story of the Silmarillion, and what are their interests and biases? This is not just an imaginary topic of the invented world, but a vital question concerning how Tolkien wrote the story. Also, what real-world influences inspired his story, and what does that say about his interests and biases?

There were also some theoretical papers which unraveled the question of whether Tolkien was racist or anti-racist, sexist or anti-sexist, and how much of each. Actually in each case he was both, and you won't understand him until you've figured that out. I see it as that Tolkien's instincts were fairly egalitarian, but he had drunk deeply of the racial and sexual cantish rhetoric of his time and absorbed it as his own.

And, of course, many wise ones maintain that it doesn't matter what the author intended, it matters what the readers see. This perspective has its value, but I see it as limited. Some readers aren't paying close attention and just misread. Others are exploiting the work for their own ends and desires. They should acknowledge that cheerfully, and some do. These cases say a lot more about the readers than about the work. But even leaving those aside, I don't favor blaming the author for readings that only come into favor decades later.

Much to chew on. Glad I heard as much as I did.

Very good stuff, though, focusing on obscure literature of Middle-earth's Second Age. Gratifyingly advanced presentations, assuming the auditors knew not only Tolkien's writings in detail but the scholarly literature as well. I particularly liked two papers performing some deep character analysis of Aldarion and Erendis. I claim that Erendis is Tolkien's greatest female character. If she's unfamiliar to you, you should read Unfinished Tales, which I think is the posthumous Tolkien book that the most fans of The Lord of the Rings would most like. I've written about her myself, but mostly to introduce her to the unfamiliar, not at the advanced level heard here.

A couple speakers, including the keynoter, explored a topic which has gotten a lot of discussion over the years, the internal sources of the history. Who is telling the story of the Silmarillion, and what are their interests and biases? This is not just an imaginary topic of the invented world, but a vital question concerning how Tolkien wrote the story. Also, what real-world influences inspired his story, and what does that say about his interests and biases?

There were also some theoretical papers which unraveled the question of whether Tolkien was racist or anti-racist, sexist or anti-sexist, and how much of each. Actually in each case he was both, and you won't understand him until you've figured that out. I see it as that Tolkien's instincts were fairly egalitarian, but he had drunk deeply of the racial and sexual cantish rhetoric of his time and absorbed it as his own.

And, of course, many wise ones maintain that it doesn't matter what the author intended, it matters what the readers see. This perspective has its value, but I see it as limited. Some readers aren't paying close attention and just misread. Others are exploiting the work for their own ends and desires. They should acknowledge that cheerfully, and some do. These cases say a lot more about the readers than about the work. But even leaving those aside, I don't favor blaming the author for readings that only come into favor decades later.

Much to chew on. Glad I heard as much as I did.